Seto Naikai to

Nagasaki

|

Cruising

Seto Naikai, the Inland Sea of Japan, is an unusual experience for most

cruisers from other countries. These days it is true that in many developed

countries you not only do not need to anchor to go cruising, but are actively

discouraged or prevented from using it. However, most long-term cruisers are

used to spending long periods moving from anchorage to anchorage. There is

none of that in Japan. Virtually every cove or nautical nook has already been

turned into a fishing harbour, with tons of concrete lining the shore. There

are a few open roadsteads where it might be possible to anchor, but not

particularly safe, and in any case many are taken up with aquaculture of one

kind or another. There are relatively few marinas even in southern Japan and

those few often charge outrageous rates for visitors. Gone are the days when

virtually every Japanese marina gave foreign yachts a week’s free mooring. As

a result, cruisers tend to move from one harbour to the next, usually finding

space either alongside a dock wall or a rusty, disused pontoon. Naturally the

most sheltered spots are almost always taken by local fishing boats or the

few local yachts, so visitors have more exposed berths often bounced around

by the wash from passing vessels. |

|

|

|

The

overwhelming impression of the shore-line of Seto Naikai is of industry.

There are the smoke stacks of huge industrial plants everywhere along the

shore, as well as huge shipyards, some of them even on quite small islands.

In contrast, are the slightly more rural islands which dot the Sea. These are

mostly rocky and vary widely in size. Many have been the sites of quarries

which supplied the stone from which the many feudal castles of southern Japan

were built. The economies of most of the islands are now dependent largely on

fishing and tourism. Fortunately the Japanese are great consumers of fish and

also great tourists in their own country. Nevertheless, many of the islands

are suffering severe de-population, despite the best efforts of the

government to provide infrastructure to the aging inhabitants. |

|

The

other factor which dominates a cruiser’s sailing plans in Seto Naikai as well

as in much of Japanese waters is the constant presence of very large numbers of

fishing boats, small and large, undertaking all kinds of fishing, from

trawling and long-lining to stationary squid fishing with sun-rivalling,

powerful lamps. Particularly difficult to cope with until you are used to

them are the pair trawlers. In Japan, the commercial fishermen reign supreme.

Not only must you stay out of their way, but also avoid getting involved with

any of the gear which they may set out. If you interfere with their work or

damage their gear or boat, you are liable not only for the repairs or

replacement, but also for consequential costs and loss of earnings, which can

be huge. Sailing at night in Seto Naikai is not advisable as a result. |

|

|

|

Even

in early spring, there is little wind in the Inland Sea and in summer even

less – unless there is a typhoon, when there is far too much! In general, you

motor. This is just as well, as the many narrow channels between the islands

often have very strong tidal currents. Getting your tides right is pretty

important even when motoring, as some can run up to 6-7 knots at springs.

Though Japanese modern architecture often leaves a good deal to be desired,

their bridges are often very beautiful. There are plenty of these to

contemplate in Seto Naikai, as many of the islands in the central part of the

sea are now joined by bridges, giving access to both Honshu Island to the

north and Shikoku to the south. |

|

We

were sad to depart our winter base at Tannowa, where we had made friends and felt

right at home. Yoshida San even came down in the still dark March 5 dawn to

see us off and take a last few photos for the Yacht Club news sheet. That day

was like a number to follow, motoring over calm seas through crowds of

fishing boats, past vistas of industry. We stopped at Kiba and Shodoshima,

the latter in pouring rain, wandered through their respective undistinguished

towns, but did marvel at Shodoshima’s huge supermarket which contrasted

sharply to its quirky nightclubs close by and the equally ‘cute’ tourist

ferry bringing visitors to the island. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Our

stop at Takamatsu on the north coast of Shikoku, was much more interesting.

Like most larger Japanese cities, it had been flattened by American bombing

toward the end of WWII. Taking the opportunity, this city unlike some others

had been rebuilt in fairly elegant fashion with broad avenues and pavements

wide enough to accommodate easily both pedies and cyclists. Courtesy of a

friendly local diver we found a berth alongside his boat in the well

protected fishing harbour, avoiding both the expense and discomfort of the

so-called marina. There were beautiful traditional gardens and free wifi at

the well appointed and comfortable foreign exchange centre. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vicky

had read Alex Kerr’s book ‘Lost Japan’ with pleasure and interest. As a

result, she was keen to see the area of Shikoku, where he had established a

centre to preserve some of the traditional aspects of Japanese rural life. We

hired a tiny ‘yellow plate’ car (engines under 660cc) and set off fearfully

for our first experience of Japanese traffic. In fact there is little to

fear. The cars are mostly small and under-powered, the speed limits are so

low that no one pays attention to them, but nevertheless travels at speeds

which frustrate most European or American drivers and almost everyone is very

polite if not particularly skilled. However, many of the roads are very

narrow. Useful land is at a premium and not to be wasted on wide roads or

motorways. Vicky did her usual trick of planning a route which took in as

many single track roads as possible, through scenery which the driver

couldn’t view for fear of running into either a gorge on one side or one of

the exceptionally deep open drains which verge Japanese country roads on the

other. It was all quite exciting, though perhaps not all that rural to

western eyes, given the Japanese tendency to build large concrete structures

where ever they can find space and have an inclination to build, even if the

surrounding scenery is beautiful and would rather not be spoiled. |

|

|

|

|

|

Though it was spring on the coast, it was still very wintery inland in the mountainous centre of Shikoku. We donned our hiking boots for a trek up a snowy mountain side in brilliant sunshine. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

snow was falling in considerable quantities on the morning we left our

pleasant over-night stop at a backpacker-style ryokan. We nearly didn’t make

it up the steep narrow road to Chiiori, but were glad we did in the end.

Paul, the current residential manager gave us an interesting tour and we

gained a bit more insight into both traditional rural Japan and into Alex

Kerr’s approach to the conservation of some aspects of its life. On

the way back to Takamatsu we visited the well known shrine at Konpira, which

is devoted to seafarers. In the usual inappropriate way, this is nowhere near

the sea and requires a climb up hundreds of steps. At Tom’s mis-directed

insistence we even climbed all the way up to the top shrine, devoted to the

Emperor – 1400 steps up and back in all. Just for luck, we pinned up a photo

of ‘Sunstone’ at the seafarers’ shrine. When we got back to the boat we heard

on the BBC World Service the dreadful news about the devastating earthquake

and tsunami at Sendai in north-eastern Honshu. We later gathered that the

quake occurred only two minutes after our visit to the Konpira shrine. That

evening there were tsunami warnings even in Seto Naikai, though there was

nothing felt as far in as Takamatsu. The next day at the foreign exchange

centre, we saw some of the CNN filmed reports of the tsunami. Like everyone

else we were stunned and disbelieving seeing the incredible power,

destruction and loss of life. As non-Japanese speakers we were at a loss to

communicate our feelings to the Japanese we met. Despite the fact that quite

a few people left Tokyo after the quake, most did not. Though the Japanese

are to some extent inured to the impact of these natural disasters, which

occur in the country quite often, even they seemed shocked and taken aback by

the extent of this disaster. Whenever we said that we lived in New Zealand

there was a shared sense of national tragedy, given the recent earthquakes

and loss of life in Christchurch. We

found the reaction of those in other countries more surprising, particularly

after it became apparent that there were severe problems at the Fukushima

nuclear power plant. It seemed to us that the level of panic was in inverse

proportion to the distance from the events. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nao Shima, our next stop was only a short hop away

and was very interesting and even entertaining. Though the island had a large

cement works at one end, the remainder of the island was devoted to modern

art. A wealthy patron had established a hotel with an associated museum,

featuring works by a variety of well known modern artists, including David

Hockney. The museum itself was also housed in a very interesting building.

Works of art were dotted liberally around the southern side of the island,

all within reasonable walking – or in our case, biking - distance of the

ferry and ‘Sunstone’. The most entertaining feature of this devotion to art,

was the public onsen – baths – which had a very fanciful and eccentric

façade, while inside there were tiled works and photos as well as the statue

of an elephant bestriding the wall between the men’s and women’s baths. We

were fortunate to visit at neap tides, as our berth along the wall in the

fishing harbour would have been too shallow at springs. This was also our

first chance to try out our large, orange, polystyrene fenders, which are a

feature of Japanese harbours, though not a particularly ‘green’ one. With

barnacles and rough walls they were essential. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We

had been told that we would get a warm welcome at Kitagishima from Colin

Ferrell, an expatriate Canadian and his Japanese wife, Mika, who run a marine

supply and sail-making business on the island. In fact, the welcome was even

warmer because our New Zealand cruising friend, Fenton Hamlin, had taken up

temporary residence with his boat, ‘Pateke’, while working for Colin. We had

last seen Fenton outside New Zealand at Asanvari in Vanuatu. We had a

delightful time with Colin, Mika, Fenton and Kojima, as well as hiking around

much of the island. As we walked we passed scores of now defunct stone-cutting

businesses. At one time the island’s quarries produced huge quantities of

high quality granite for ornamental stones, but the market collapsed and with

it the island’s economy and population. All round the island are heaps and

heaps of beautiful, but abandoned stone. The collapse of the market for stone

has also led to the rapid depopulation of the island. The witnesses to this

were the abandoned kindergarden and school. While the only secondary school

on the island has six students. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

At

Yuge, there is a maritime college, which is very appropriate as there are

several huge shipyards within sight of its harbour on nearby islands. The

mayor of the island is determined to encourage visiting yachts and the

harbour boasted a well equipped and protected floating dock, where we joined

our Dutch friends, Hendrik-Jan and Hanna of ‘Bannister’, who had already been

befriended by one of the lecturers at the college, Takanori San. Takanori

very kindly borrowed a ‘people mover’ and took the four of us cruisers on a

tour through the islands by road and across many bridges to Shikoku where we

visited the castle in Matsuyama as well as the particularly well known Dogo

Onsen. It was a very enjoyable day. To get our bodies back in motion after a

day in a car, we biked the following day up and down the island’s hills.

Vicky was already in training for a half-marathon at the beginning of April

at Saga and so did more biking than Tom as well as the occasional run. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

It

is only a short hop to Onomichi, another important shipbuilding centre.

Unfortunately it rained unrelentingly through our visit there. However,

Yamada San, another friend of Kakihara San, made us very welcome. He arranged

our berthing at a disused ferry dock, which gave us a little protection from

the huge wakes tossed by passing vessels in the channel. A small marina had

been built in the same area. The docks were well equipped and could

accommodate a number of boats. However, the wakes were bound to make the

marina very uncomfortable. With Yamada San we had further opportunities to

sample Japanese cuisine Onomichi style. The okonomiyaki, (filled pancake with

noodles) was a good deal different from that in Osaka, but still very tasty.

We decided against standing in a 50 metre queue in order to sample the

apparently famous Onomichi ramen noodles. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In rather better weather, we moved on to Hiroshima

via Omishima. At the latter we paid our first mooring fee in a small harbour,

1 Yen per ton per night, 10 Yen, which is about 13 British pence. Very

reasonable we thought! It was rather different at Hiroshima’s Kanon Marina,

but still not excessive at Y1,800 per night, (about US$22). Like many

Japanese marinas built during the boom years it is mostly empty. However, the

facilities were good and the staff very helpful. However, the marina is a

long way from the centre and we were very glad to have our bikes, which Tom

was becoming increasingly adept at assembling and dismantling as we moved

from port to port. This did give us the ability to get quickly to the centre

of the city and particularly to the Peace Park, Memorial and Museum, all of

which are dedicated to removal of all nuclear weapons from the planet. Not

surprisingly the city has gone to great lengths to memorialise the

destruction and loss of life from the explosion of the first atomic bomb. It

has done so very effectively. The Park is beautiful and the remains of the

building commonly known as the A Bomb Dome are poignant. The museum’s impact

was interesting in its account of the development of Japanese militarism

before WWII and of the events behind the decision to drop the bomb in the

USA. However, much of the museum’s exhibits are understandably devoted to the

horrific effects of the bomb. It was both an interesting and a moving

experience. |

|

|

|

|

Miyajima, not far from Hiroshima is the site of the

famous and much photographed ‘torii in the water’. We managed to find a berth

at a very rusty pontoon, but at the quiet end of town away from the ferries

and the hordes of tourists. To get even further away from them we took one of

the steep hiking trails up to the top of Mt. Misen. There were hundreds of

tourists at the top who had taken the cable car, but we passed no one on our

hike. The Japanese diet keeps most people fairly slim, but it is not

generally as a result of exercise. The favourite Japanese male sport is golf,

mostly practised on the driving range, while youngsters play baseball, which

is not outstandingly aerobic. To be fair there are lots of Japanese

long-distance runners, as Vicky was to find, as well as many devoted older

hikers. By the time we got down from the mountain it was nearly time for the

sunset photo-op of the torii. Vicky went along and found to her astonishment

that a tour boat was allowed to wander between the uprights of the torii at

the critical time, thus spoiling all the photographers ashore their chances

of the ‘perfect shot’. |

|

|

|

|

|

Himeshima

is a pleasant little island off the north coast of Kyushu. It boasts two or

three fishing villages and little or no attempts at tourism apart from one

annual festival. Despite a busy fishing coop, it was a quiet place. The

greatest excitement was watching the skilled ferry captain spinning his ship

in it own length in order to dock in the little harbour. We found it pleasant

and relaxing after the bustle of Hiroshima and Miyajima. We took a short hike

out of town to a rugged outcrop against which the waves of a brisk westerly

shattered themselves. A diminutive, simple shrine stood on this isolated

outcrop with a gnarled tree clinging to the rock. It was something straight

from a traditional Japanese painting. |

|

|

|

|

We had dithered for some time over just where to

make our final stop in Seto Naikai and, in addition, where to leave the boat

so that Vicky could make her trip to Fukuoka for the Saga half-marathon. The

most convenient marina to Kanmon Kaikyo, the Shimonoseki strait leading into

the Sea of Japan, proved on enquiry to be ridiculously expensive, so we

settled on Ube, an industrial port about 10 miles from the Kaikyo. The first

sight of the town from the water is not at all encouraging. The whole

waterfront is dominated by huge industrial works, which we later gathered

were mostly chemical plants. The scene smacked of ‘dark satanic mills’.

Surprisingly the town itself only a few streets in from the waterfront proved

to be devoted to flowers and had some of the poshest shops we had seen since

Osaka. The Ube Marina was not really a marina at all in our terms, but merely

a facility for craning motorboats in and out of the water for owners use at

weekends. There was one small pontoon, used for boats about to be craned.

However, the manager, Amiya San, was taken with Vicky’s determination to do

the half-marathon and found space for us at two different pontoons of varying

fragility. In this uncertain situation Tom decided to stay with the boat and

Vicky headed out by bus. Despite a slightly off-hand manner, Amiya San proved

a soul of hospitality, taking Tom out to lunch at a local sushi ‘conveyor

belt’ restaurant in Vicky’s absence. The only real downside of the berth was

the departure of the fishing fleet at exactly 0500 every morning. |

|

|

|

|

|

Vicky has run half-marathons in Vancouver, BC, Nelson,

NZ, as well as Auckland. To increase her world-wide coverage she was keen to

run in Japan. Of course the problem is training while cruising, so every time

we stopped at a small island Vicky would run across it or up and down it,

depending on the length or breadth. It was a two-hour bus trip to Fukuoka

from Ube. We had originally heard about the run from Jaap and Marijke,

long-term cruisers from Holland, who have been based in Japan for many years

now. They keep their boat, ‘Alishan’ in Fukuoka and so Vicky was able to stay

with them and join their Japanese running group. It was a 1½ hour bus trip to

Saga on a perfect running day. The marathon is scheduled at this time of

year, early April, to coincide with the cherry blossoms, which line the flat

route for the 7,000 runners. Quite unexpectedly, Vicky managed her best time

ever, a few seconds under two hours – a pretty good achievement considering

her relatively light training. On the bus trip back the very welcoming group

stopped for a lunch of carp, sashimi style, with a reviving onsen at the end

of the day. |

|

|

|

|

|

The morning after Vicky’s return, we made a very

early start to clear Ube before the fishing fleet and to make the first of the

fair tide through the Kanmon Kaikyo. It was a long day to get to Fukuoka. The

Kaikyo has a fearsome reputation for very strong tides. Fortunately, we made

our transit at a time of relatively weak tides and not at the height of the

tide. The whole of the strait is lined with industry, everything from steel

works and shipyards to refineries, and ship traffic, small and large, is

continuous. In the event, the passage

of the strait was less daunting than the much shorter but extremely narrow

channel south of Hiroshima and Kure. Having motored clear of the strait we

picked up a brisk quartering breeze that whisked us to Fukuoka by

mid-afternoon, far earlier than we had expected. It was our first proper sail

in a month. Fukuoka gave us several ‘firsts’. It was our first

port outside the Inland Sea. It was our first experience of cherry blossom

time in Japan and it was our first proper cruiser gathering in Japan since

Tannowa. Australians, Jon and Pam, on ‘Tweed’ had spent the winter in Fukuoka

and were happy to see some new faces even if they were Poms. ‘Bannister’

pulled in the next day and Jaap and Marijke of ‘Alishan’ acted as local

hosts. Though the facilities of Odo Marina were a bit rudimentary, the

manager was very helpful and the berth was wide enough that when a warm and

pleasant day popped up it was possible to varnish the side of the boat, which

had had no attention since November. We knew it would be last varnish we

would get on the hull until August. Local sailors made us welcome too –

Masashi San, Sakae San and Mena San. We pottered with boat jobs, sorted

cruising permits for the west coast of Honshu and dined and drank with

cruising friends. It was quite like normal cruising life. |

|

|

|

|

|

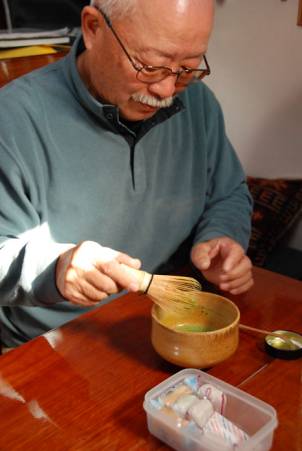

Tea master, Masashi San, whisking

traditional Japanese green tea. |

|

|

|

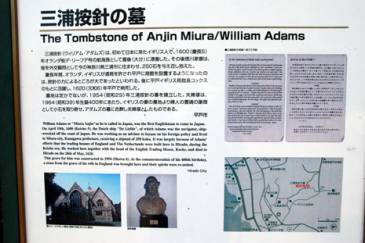

However, time was beginning to exert its pressures

and we felt that if there was to be any chance of visiting Goto Retto as well

as Nagasaki, then we had better keep moving. Hirado is one of several places

in Japan which lays claim – in this case justifiably - to being the first to

encourage trade with foreigners. It is also the resting place of Anjin San,

William Adams, an English mariner who was shipwrecked in Japan and became an

adviser to Eiyesu Tokugawa, the founder of the Shogunate, which ruled Japan

from the early 1600’s until 1867. Anjin San is also the basis for the central

character of James Clavell’s novel ‘Shogun’. The town of Hirado is quite

small. The harbour sits on the east side of the island on the edge of a

tide-swept strait. Above the town there is an attractive castle, which, like

virtually all castles in Japan, is a concrete reconstruction of the original.

Our visit to Hirado was enlivened by Kidera San, another of Kakihara San’s

many friends. Though he spoke little English he was a lively companion, and

when he and his fisherman friend took us out to dinner at a local hotel we

had a hilarious time, with litres of alcohol consumed by the two Japanese,

followed by a late night dram on ‘Sunstone’. How they managed it we do not

know, but the next morning Kidera and his friend shepherded us out of the

harbour and waved goodbye as we headed for Nagasaki. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In

Nagasaki we had our first real taste of heavy-weight Japanese officialdom.

Despite dire warnings, throughout Seto Naikai we hardly saw a single official

until we got to Hiroshima and Ube. In Nagasaki, it was clear that officials took

their responsibilities very seriously. We were interrogated by one

particularly bumptious young immigration officer who seemed to feel that we

had somehow been illegitimately granted an extension to our visas. There were

no problems in the end, but it all took a long time. Unfortunately, Dejima

Marina in the centre of town is also adjacent to the ferry docks. As a

result, the wash from ferries can be quite vicious, heaving boats around

terribly. This and the next day’s weather forecast for the coming week

decided us on a change of plans. It was clear that if we stayed we would be

stuck in the area for some time, perhaps 10 days, which we could not afford.

We realised that we should have gone straight north from Hirado and decided

to do our penance by making a night passage directly up to Tsushima, a large

island in the Korea Strait, actually slightly closer to Korea than Japan.

After a quick refuelling we headed off into pleasant late afternoon sunshine. |

Next |